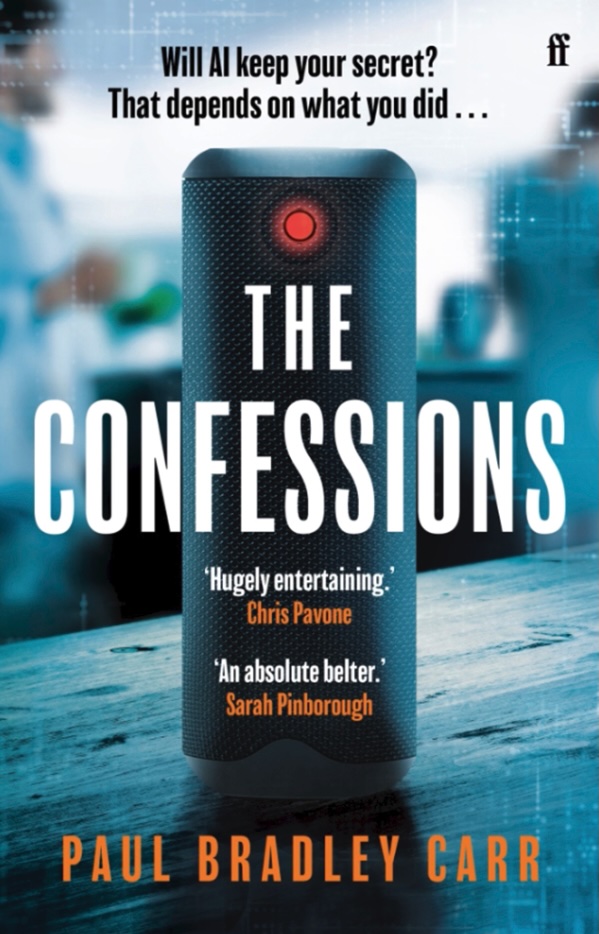

OUT NOW: THE CONFESSIONS Atria (USA/Canada) and Faber & Faber (UK/Commonwealth)

**** AN INSTANT USA TODAY BESTSELLER! ****

"A terrifying window into the future." - NEW YORK TIMES (BEST SUMMER THRILLERS)

"A superb and timely thriller grounded in relatable issues and horrifyingly plausible." - THE GUARDIAN (BEST THRILLERS OF 2025)

"A top-notch technothriller, reminiscent of the best of Michael Crichton and Tom Clancy." - LOS ANGELES TIMES

|  |